Introduction to Nutrition and Dietetics

[Source: doh.as]

Definition and Importance

Nutrition and dietetics is a field that focuses on the study of food and its effects on health. [#1] This scientific discipline examines how nutrients affect the body at molecular, cellular, and systemic levels. The importance of this field cannot be overstated—it forms the foundation of preventive healthcare and plays a critical role in disease management.

While nutrition deals with the science behind how food nourishes our bodies, dietetics involves the application of nutritional science to individuals and groups to promote health and manage disease. These complementary aspects work together to create comprehensive approaches to human health through dietary interventions.

The significance of nutrition and dietetics extends beyond individual health to public health systems worldwide. Proper nutritional knowledge helps combat widespread issues like obesity, diabetes, and cardiovascular diseases. For healthcare professionals, understanding these principles allows for more effective patient care and treatment planning.

Historical Perspective

The study of nutrition has ancient roots. Early civilizations recognized connections between food and health, though they lacked scientific understanding of why certain foods affected the body in specific ways. Hippocrates, often called the father of medicine, famously advised, Let food be thy medicine and medicine be thy food—an early acknowledgment of nutrition’s healing potential.

Modern nutrition science began taking shape in the 18th century with the discovery of oxygen and its role in metabolism. The 19th and early 20th centuries brought breakthroughs in identifying essential nutrients, vitamins, and minerals. These discoveries revolutionized our understanding of how food affects health and led to solutions for previously mysterious conditions like scurvy and beriberi.

The profession of dietetics emerged in the early 20th century, primarily in hospital settings where specialized diets became recognized as therapeutic tools. World Wars I and II further highlighted the importance of nutrition when food rationing required careful planning to maintain population health with limited resources.

Scope and Interdisciplinary Nature

Today’s nutrition and dietetics field spans numerous domains:

- Clinical nutrition: Focusing on nutritional therapy for patients with various medical conditions

- Community nutrition: Addressing nutritional needs across populations

- Food service management: Overseeing food preparation in institutional settings

- Sports nutrition: Optimizing dietary intake for athletic performance

- Research: Advancing nutritional science through rigorous studies

- Education: Teaching nutritional principles to professionals and the public

The interdisciplinary character of nutrition and dietetics makes it exceptionally dynamic. Professionals in this field collaborate with experts from biochemistry, physiology, psychology, sociology, and public health. This cross-disciplinary approach allows for comprehensive solutions to complex health challenges.

Advances in genetics have introduced personalized nutrition—tailoring dietary recommendations based on an individual’s genetic makeup. Meanwhile, environmental concerns have expanded the field to include sustainability considerations, examining how dietary choices impact not just human health but planetary wellbeing.

As we continue to face global health challenges, nutrition and dietetics professionals serve as key players in developing strategies for better health outcomes. Their expertise helps shape policies, programs, and individual interventions that promote optimal nutrition throughout the lifespan.

Fundamentals of Nutrition Science

[Source: nutrition.rutgers.edu]

Core Concepts and Principles

Human nutrition is the scientific study of how food and drink affect our health and wellbeing. [#2] This field examines the complex relationships between dietary intake and bodily functions, forming the backbone of preventive healthcare approaches worldwide. Understanding these fundamental principles helps individuals make informed choices about their diet and lifestyle.

At its core, nutrition science revolves around several key principles. The concept of energy balance—calories consumed versus calories expended—determines whether an individual maintains, gains, or loses weight. This balance varies based on factors like age, sex, activity level, and metabolic rate. Another foundational principle involves nutrient density, which measures the amount of beneficial nutrients relative to the energy content of foods.

Bioavailability represents another crucial concept, referring to how efficiently the body can absorb and utilize nutrients from different food sources. For instance, iron from animal products (heme iron) is more readily absorbed than iron from plant sources (non-heme iron). These differences significantly impact dietary recommendations, particularly for specific populations like vegetarians or those with absorption disorders.

Role of Nutrients in the Body

Nutrients are substances in food that are essential for the growth, maintenance, and repair of the body. Without adequate nutrient intake, various bodily functions can become compromised, leading to deficiencies and health complications. Each nutrient serves specific purposes within our physiological systems.

There are six classes of nutrients: carbohydrates, proteins, fats, vitamins, minerals, and water. These can be further categorized as macronutrients (needed in larger amounts) and micronutrients (required in smaller quantities). Let’s examine each class:

- Carbohydrates: Primarily provide energy, supplying 4 calories per gram. They range from simple sugars to complex starches and fiber. While simple carbs offer quick energy, complex carbs provide sustained fuel and often contain additional nutrients.

- Proteins: Composed of amino acids, proteins yield 4 calories per gram and serve as building blocks for tissues, enzymes, hormones, and antibodies. Complete proteins contain all essential amino acids, while incomplete proteins lack one or more.

- Fats: The most energy-dense nutrient at 9 calories per gram, fats insulate organs, transport fat-soluble vitamins, and provide essential fatty acids. Different types (saturated, unsaturated, trans) affect health in various ways.

- Vitamins: Organic compounds required in small amounts for normal metabolism, growth, and development. Fat-soluble vitamins (A, D, E, K) can be stored in body tissues, while water-soluble vitamins (B complex, C) generally cannot.

- Minerals: Inorganic elements needed for various bodily functions. Major minerals like calcium and magnesium are required in larger amounts, while trace minerals such as zinc and selenium are needed in smaller quantities.

- Water: Often overlooked yet absolutely vital, water comprises about 60% of the human body and facilitates countless biochemical reactions, temperature regulation, and waste removal.

The interplay between these nutrients creates a complex system where balance is key. For example, vitamin D helps calcium absorption, while vitamin C enhances iron uptake. These synergistic relationships highlight why varied diets typically outperform single-nutrient supplements for overall health.

Nutrition Across the Lifespan

Nutritional needs fluctuate dramatically throughout life, reflecting the changing physiological demands of different life stages. These variations necessitate adjustments in both the quantity and types of nutrients consumed at different ages.

During pregnancy, requirements for certain nutrients like folate, iron, and calcium increase substantially to support fetal development and maternal health. Folate is particularly critical in the first trimester to prevent neural tube defects. Breastfeeding mothers need additional calories and nutrients to produce milk while maintaining their own health.

Infancy represents a period of rapid growth requiring nutrient-dense foods. Breast milk or formula provides complete nutrition for the first months, gradually complemented by solid foods. Toddlers and young children need proportionally more nutrients per kilogram of body weight than adults, supporting their developing brains and bodies.

Adolescence brings another growth surge with increased caloric and nutrient demands, particularly for calcium, iron, and protein. Boys and girls develop different nutritional needs during this stage, with menstruating females requiring more iron and males needing more calories and protein to support muscle development.

Adult nutrition focuses on maintaining health and preventing chronic disease. Middle age often brings metabolic changes requiring adjustments in caloric intake to prevent weight gain. For older adults, protein becomes increasingly important to preserve muscle mass, while calcium and vitamin D help maintain bone density. Absorption efficiency may decrease with age, potentially necessitating higher intake of certain nutrients.

Throughout all life stages, individual factors like genetics, activity level, health status, and even gut microbiome composition can influence nutritional requirements. This variability underscores the importance of personalized approaches to nutrition rather than one-size-fits-all recommendations. Understanding these fundamental principles of nutrition science provides a framework for making informed dietary choices at every stage of life.

Educational Pathways in Nutrition and Dietetics

[Source: swcahec.org]

Bachelor of Science Degree in Nutrition

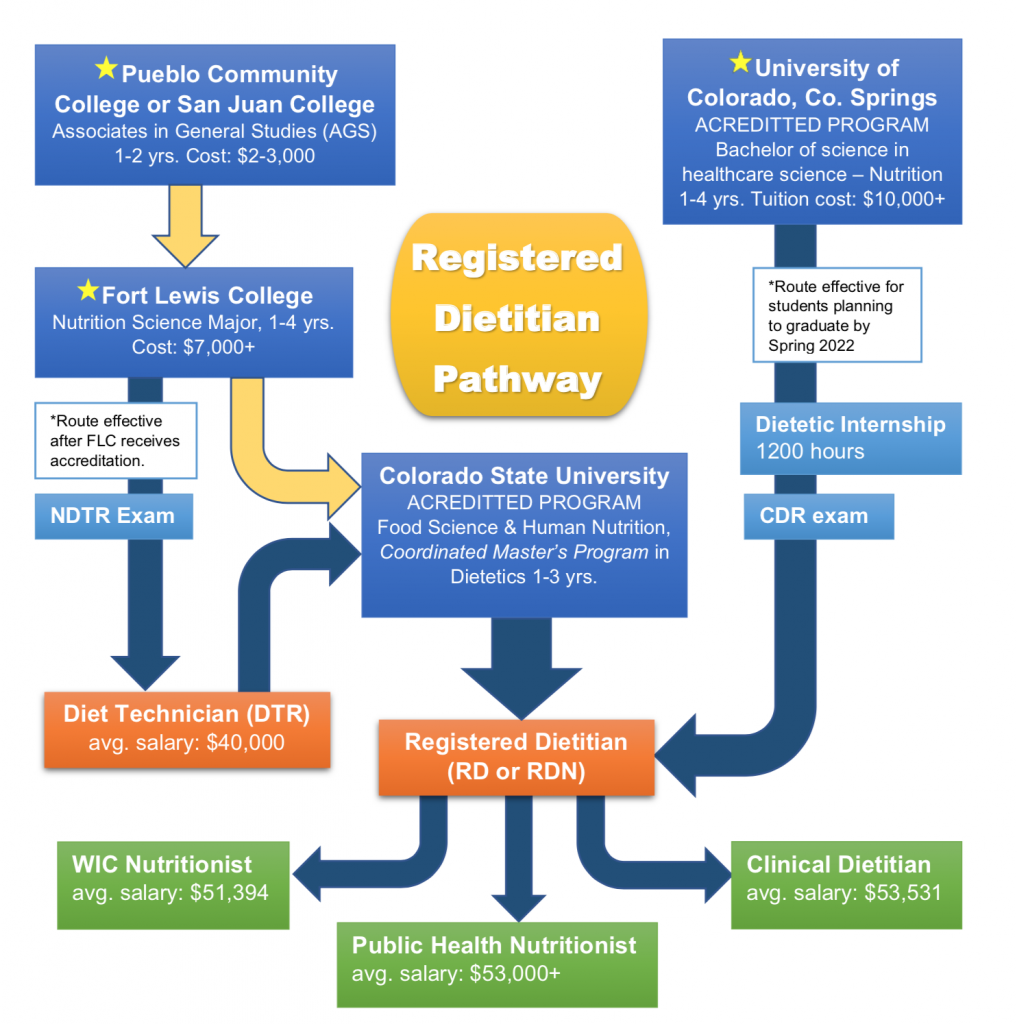

The foundation of a career in nutrition and dietetics typically begins with a Bachelor of Science degree in Nutrition Science or a related field. These undergraduate programs provide students with comprehensive knowledge of the scientific principles that govern human nutrition, food composition, and the relationship between diet and health outcomes. Most programs combine theoretical classroom learning with practical laboratory experiences to develop both analytical and applied skills.

A typical Bachelor’s curriculum includes core courses in:

- Basic Sciences: Biology, chemistry, biochemistry, and anatomy provide the scientific foundation necessary to understand nutritional processes in the human body.

- Nutrition-Specific Courses: Food science, nutrient metabolism, medical nutrition therapy, and community nutrition form the specialized knowledge base.

- Social Sciences: Psychology, sociology, and anthropology help students understand the complex social and behavioral factors that influence food choices and eating patterns.

- Professional Skills: Communication, counseling techniques, and ethics prepare students for client interactions in professional settings.

Many programs also incorporate supervised practice experiences or internships that allow students to apply their knowledge in real-world settings. These practical components are particularly valuable for developing professional competencies and building networks within the field. Some institutions offer coordinated programs that integrate the didactic coursework with the required supervised practice hours needed for professional credentialing.

Program Outcomes and Skills Acquired

Nutrition and dietetics education aims to develop professionals who can translate complex scientific concepts into practical dietary advice for individuals and communities. Graduates of these programs acquire a diverse set of skills that prepare them for various professional roles.

Key competencies developed through nutrition education include:

- Scientific Literacy: The ability to interpret and evaluate nutrition research, distinguish credible information from misinformation, and apply evidence-based practices.

- Assessment Skills: Techniques for evaluating nutritional status through anthropometric measurements, dietary analysis, and interpretation of biochemical data.

- Intervention Planning: Developing personalized nutrition plans based on individual needs, health status, and cultural preferences.

- Communication: Translating technical nutrition information into clear, actionable guidance for diverse audiences with varying levels of health literacy.

- Critical Thinking: Analyzing complex nutritional problems and developing appropriate solutions based on scientific evidence and client-specific factors.

These programs also foster professional attributes such as ethical reasoning, cultural sensitivity, and interdisciplinary collaboration—qualities essential for effective practice in healthcare and community settings. Students learn to recognize the limitations of their knowledge and develop habits of lifelong learning necessary in a field where scientific understanding continuously evolves.

Advanced Studies and Specializations

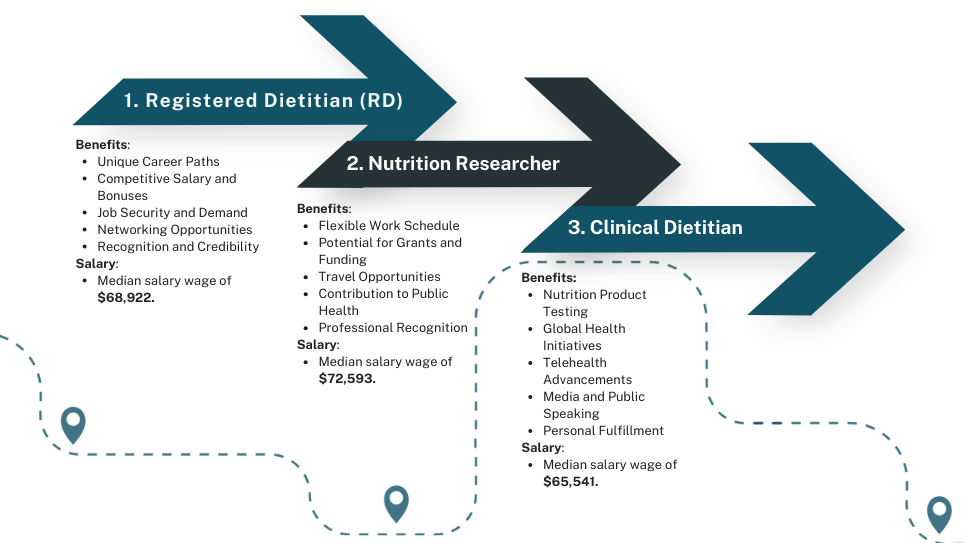

For many nutrition professionals, education extends beyond the undergraduate level. Advanced degrees offer opportunities for specialization and can significantly expand career prospects. A Master of Science (MS) in Nutrition and Dietetics involves advanced study in nutrition science, diet planning, and health promotion. [#3] These programs often emphasize research methods and may require completion of a thesis or capstone project.

Common areas of specialization at the graduate level include:

- Clinical Nutrition: Focused on medical nutrition therapy for complex conditions like diabetes, cardiovascular disease, or renal disorders.

- Public Health Nutrition: Addressing population-level nutrition issues, program planning, and policy development.

- Sports Nutrition: Optimizing nutritional strategies for athletic performance, recovery, and injury prevention.

- Pediatric Nutrition: Specializing in nutritional needs and interventions for infants, children, and adolescents.

- Gerontological Nutrition: Focusing on the unique nutritional requirements and challenges of older adults.

- Food Service Management: Combining nutrition expertise with business and management skills for institutional food service operations.

Doctoral programs (Ph.D.) in nutrition prepare students for careers in research and academia, contributing to the advancement of nutrition science through original investigations. These programs require significant independent research culminating in a dissertation that adds new knowledge to the field.

Beyond formal degree programs, continuing education plays a vital role in professional development. Registered Dietitian Nutritionists must complete continuing education requirements to maintain their credentials, keeping their knowledge current with emerging research and practices. Specialized certifications in areas like oncology nutrition, renal nutrition, or diabetes education allow practitioners to demonstrate expertise in specific practice areas.

Graduates of nutrition science programs have numerous pathways available after completing their studies. Many pursue careers as dietitians or nutritionists, while others use their education as a stepping stone to additional professional training. The foundational knowledge gained through nutrition education serves as excellent preparation for further academic studies in dietetics, medical, dental, occupational/physical therapy, pharmacy, and advanced graduate study in nutrition science. [#4]

The educational journey in nutrition and dietetics reflects the field’s interdisciplinary nature, combining scientific rigor with practical application skills. This comprehensive preparation equips graduates to address the complex nutritional challenges facing individuals and communities in contemporary society, whether through direct patient care, public health initiatives, research, or education.

Career Opportunities in Nutrition and Dietetics

[Source: careersidekick.com]

Typical Employment Opportunities

The field of nutrition and dietetics offers diverse career paths that extend far beyond the traditional clinical setting. Professionals in this discipline can apply their expertise in numerous environments, addressing nutritional needs across different populations and contexts.

Healthcare remains a primary employment sector for nutrition professionals. In hospitals, dietitians assess patients’ nutritional status, develop therapeutic meal plans, and collaborate with medical teams to optimize patient outcomes. Long-term care facilities employ nutrition experts to address the specific dietary needs of elderly residents, while outpatient clinics provide opportunities for counseling individuals with chronic conditions like diabetes or heart disease.

Nutritionists and dietitians often work in healthcare settings, community programs, and private practice. This flexibility allows professionals to choose environments that align with their interests and strengths. Some prefer the fast-paced clinical environment, while others thrive in community-based roles or independent consulting.

Beyond clinical practice, nutrition professionals find fulfilling careers in:

- Food Service Management: Overseeing nutritional quality and food safety in institutional settings like schools, corporate cafeterias, and correctional facilities.

- Public Health: Developing and implementing nutrition programs at local, state, or federal levels to address population health concerns.

- Education: Teaching nutrition principles in academic institutions or conducting community education programs.

- Research: Contributing to scientific knowledge through clinical trials, laboratory studies, or epidemiological research.

- Corporate Wellness: Designing and managing nutrition components of employee wellness programs.

- Food Industry: Applying nutrition expertise in product development, marketing, or regulatory compliance.

The sports and fitness industry has also become a significant employer of nutrition professionals. Sports dietitians work with athletes at all levels to optimize performance, support recovery, and maintain health. This specialized area combines nutrition science with exercise physiology to create personalized fueling strategies for competitive and recreational athletes alike.

Emerging Trends and Future Prospects

The career landscape for nutrition professionals continues to evolve, shaped by scientific advances, technological innovations, and shifting health priorities. Several trends are creating new opportunities in this field:

- Telehealth and Digital Nutrition Services: Virtual platforms have expanded access to nutrition counseling, allowing practitioners to reach clients regardless of geographic location. This trend accelerated during the COVID-19 pandemic and continues to transform service delivery models.

- Personalized Nutrition: Advances in nutrigenomics and microbiome research are driving interest in individualized dietary recommendations based on genetic profiles and gut bacteria composition.

- Food Technology: The growing market for plant-based alternatives, functional foods, and sustainable food systems creates demand for nutrition experts who can bridge science and consumer needs.

- Corporate Wellness Expansion: Organizations increasingly recognize the connection between nutrition, employee health, and productivity, leading to more positions for workplace wellness specialists.

- Aging Population: The demographic shift toward an older population increases the need for nutrition professionals specializing in healthy aging and management of age-related conditions.

Graduates can pursue careers in healthcare, sport and fitness industry, food technology, biomedical and laboratory research, government nutrition services, cooperative extension, food and agriculture industry, nutraceutical industry, and non-profit nutritional support programs. This breadth of opportunities allows nutrition professionals to apply their knowledge in sectors that align with their personal interests and professional goals.

The integration of nutrition into preventive healthcare strategies presents particularly promising career prospects. As healthcare systems worldwide shift focus from treatment to prevention, nutrition professionals play an increasingly central role in addressing chronic disease through dietary intervention. This paradigm shift expands opportunities in primary care settings, where dietitians work alongside physicians to manage conditions like hypertension, diabetes, and obesity.

Professional Roles: Dietitians vs. Nutritionists

Understanding the distinction between dietitians and nutritionists is important for those considering a career in this field. While these terms are sometimes used interchangeably, they represent different levels of regulation and scope of practice in many countries.

Registered Dietitian Nutritionists (RDNs) in the United States must complete:

- A bachelor’s degree from an accredited program

- Supervised practice experience (typically 1,000+ hours)

- A national examination

- Continuing education to maintain registration

This rigorous credentialing process qualifies RDNs to provide medical nutrition therapy and work in clinical settings. Many states also require dietitians to obtain licensure, adding another layer of professional regulation.

The term nutritionist, by contrast, has varying definitions depending on location. In some regions, nutritionist is a protected title requiring specific qualifications, while in others, anyone can call themselves a nutritionist regardless of education or training. This distinction affects employment opportunities, as many healthcare facilities and insurance providers specifically require the RDN credential.

Beyond these broad categories, numerous specialized credentials exist for nutrition professionals who focus on particular areas. Examples include Certified Specialist in Sports Dietetics (CSSD), Certified Diabetes Educator (CDE), and Board Certified Specialist in Pediatric Nutrition (CSP). These additional certifications can enhance career prospects and demonstrate expertise in specific practice areas.

The professional landscape also includes roles that combine nutrition knowledge with other skill sets. Food service directors, public health nutritionists, and nutrition educators may have backgrounds in nutrition science supplemented by training in management, public policy, or education. This interdisciplinary approach reflects the complex nature of food systems and health promotion.

For those passionate about nutrition science, the field offers remarkable variety in how and where to apply that knowledge. From clinical practice to food product development, from community education to scientific research, nutrition professionals can craft careers that match their strengths and interests while contributing to improved health outcomes at individual and population levels.

Nutrition Science and Wellness

[Source: amazon.com]

Integrating Nutrition into Daily Life

Nutrition science forms the foundation of personal wellness strategies that extend far beyond simple calorie counting. Applying nutritional knowledge to everyday choices creates a framework for health that supports both immediate wellbeing and long-term vitality. This practical application transforms abstract scientific concepts into tangible lifestyle practices.

Nutrition is the study of nutrients in food and how the body uses them. [#5] This fundamental definition highlights the bidirectional relationship between what we consume and how our bodies function. Effective integration of nutrition principles into daily routines requires understanding this relationship and making informed choices based on individual needs, preferences, and circumstances.

Several practical approaches help incorporate sound nutrition into everyday life:

- Meal planning and preparation: Setting aside time to plan balanced meals reduces reliance on convenience foods and improves dietary quality.

- Mindful eating practices: Paying attention to hunger cues, eating without distractions, and savoring food enhances satisfaction and often leads to better portion control.

- Strategic grocery shopping: Creating shopping lists based on nutritional goals and focusing on whole foods supports healthier eating patterns.

- Food literacy development: Learning to read nutrition labels, understand ingredient lists, and recognize marketing claims empowers consumers to make informed choices.

- Cooking skills cultivation: Developing basic culinary techniques makes preparing nutritious meals more accessible and enjoyable.

The concept of nutritional balance varies throughout life as physiological needs change. The human body requires different amounts of nutrients at different life stages. For instance, calcium needs peak during adolescence and early adulthood when bone mass is developing, while protein requirements may increase for older adults to preserve muscle mass. Recognizing these shifting needs allows for appropriate adjustments to dietary patterns over time.

Impact on Public Health

Nutrition science significantly influences public health outcomes through both individual and population-level interventions. Dietary patterns represent modifiable risk factors for many chronic diseases that burden healthcare systems worldwide. By addressing these factors, nutrition professionals contribute to disease prevention and health promotion on a broad scale.

Public health nutrition initiatives take various forms:

- Policy development: Creating regulations and guidelines that shape food environments, such as school meal standards or food labeling requirements.

- Food assistance programs: Designing and implementing initiatives that improve food access for vulnerable populations.

- Mass education campaigns: Disseminating evidence-based nutrition information through media channels to raise awareness and influence behavior.

- Environmental interventions: Modifying physical and social environments to make healthy choices more accessible, such as improving grocery store availability in underserved areas.

- Surveillance systems: Monitoring population nutritional status to identify trends and evaluate intervention effectiveness.

The economic impact of nutrition-related health conditions underscores the importance of preventive approaches. Healthcare costs associated with diet-related chronic diseases—including heart disease, type 2 diabetes, and certain cancers—represent substantial financial burdens. Investing in nutrition education and intervention programs offers potential cost savings through reduced medical expenditures and improved workforce productivity.

Community-based nutrition programs demonstrate particular promise in addressing health disparities. These initiatives often combine education with practical support, such as cooking demonstrations, community gardens, or farmers’ market incentives. By acknowledging social determinants of health and cultural contexts, these programs can reach populations that might not benefit from traditional healthcare-based interventions.

Role of Physical Activity

Nutrition science and physical activity function as complementary components of a comprehensive wellness approach. While each offers independent health benefits, their combined effect exceeds what either can accomplish alone. This synergistic relationship manifests in multiple physiological systems and health outcomes.

The interplay between nutrition and exercise affects:

- Energy balance: Physical activity increases energy expenditure, which influences caloric needs and weight management.

- Body composition: Proper nutrition supports muscle development and maintenance when combined with resistance training.

- Metabolic health: Exercise enhances insulin sensitivity and glucose metabolism, effects that proper nutrition can amplify.

- Recovery processes: Nutritional strategies can optimize post-exercise recovery and adaptation.

- Bone health: Weight-bearing exercise and adequate calcium and vitamin D intake work together to maintain bone density.

Timing of nutrient intake relative to physical activity represents an important consideration for optimizing performance and recovery. Pre-exercise nutrition focuses on providing accessible energy sources without causing digestive discomfort. Post-exercise nutrition emphasizes replenishing glycogen stores and providing protein for muscle repair. These strategic approaches help maximize the benefits derived from physical activity.

Hydration status connects nutrition and exercise performance in critical ways. Water serves as an essential nutrient that regulates body temperature, transports nutrients, and removes waste products—functions that become even more vital during physical exertion. Developing appropriate hydration strategies based on activity type, duration, intensity, and environmental conditions supports both performance and safety.

For the general population, integrating moderate physical activity with balanced nutrition creates a foundation for health that exceeds what either component could provide independently. This integrated approach addresses multiple aspects of wellness simultaneously, from cardiovascular health to mood regulation to immune function. The accessibility of walking, bodyweight exercises, and other low-cost physical activities makes this combined strategy feasible for most individuals.

Nutrition science continues to evolve in its understanding of how dietary patterns interact with physical activity to influence health outcomes. This growing knowledge base informs recommendations for both general wellness and specialized needs, such as athletic performance or rehabilitation. As research advances, the integration of nutrition and physical activity remains a cornerstone of comprehensive health promotion strategies.

Challenges and Considerations in Nutrition

[Source: vinuni.edu.vn]

Common Misconceptions

The field of nutrition is rife with misconceptions that can lead individuals astray in their pursuit of health. In an age where information proliferates rapidly through social media and other channels, distinguishing evidence-based nutrition guidance from unfounded claims becomes increasingly difficult for the average person.

Several persistent myths continue to shape public perception of nutrition:

- Quick-fix solutions: The notion that dramatic dietary changes can produce immediate, lasting results often leads to disappointment and yo-yo dieting patterns.

- Demonization of food groups: Labeling certain foods or nutrients as inherently bad oversimplifies nutrition science and can lead to unnecessary restrictions.

- Supplement superiority: The belief that nutritional supplements consistently outperform whole foods ignores the complex interactions between nutrients found naturally in food.

- One-size-fits-all approaches: Standardized diet plans that fail to account for individual differences in metabolism, genetics, and lifestyle rarely produce optimal results.

- Correlation versus causation confusion: Misinterpreting observational nutrition studies as proving causal relationships leads to premature conclusions about food effects.

Media representation of nutrition research frequently contributes to public confusion. Headlines highlighting single studies without context can create the impression of constantly changing recommendations. This phenomenon, sometimes called nutrition whiplash, undermines confidence in legitimate nutritional guidance and fosters skepticism about the field as a whole.

Combating misinformation requires both improved science communication and enhanced critical thinking skills among consumers. Nutrition professionals play a vital role in translating complex research into practical, accessible information while acknowledging areas of scientific uncertainty. Developing media literacy specifically focused on evaluating nutrition claims helps individuals navigate the information landscape more effectively.

Ethical and Cultural Considerations

Nutrition practices are deeply embedded in cultural traditions, religious beliefs, and personal values. Effective nutrition guidance acknowledges these dimensions rather than treating food choices as purely scientific decisions. Cultural competence in nutrition involves recognizing food’s role in identity, community, and heritage.

Ethical considerations in nutrition span multiple domains:

- Food justice and access: Addressing inequities in food availability and affordability that disproportionately affect marginalized communities.

- Environmental sustainability: Balancing nutritional recommendations with ecological impacts of food production systems.

- Animal welfare concerns: Respecting diverse perspectives on animal product consumption while providing evidence-based information.

- Informed consent in interventions: Maintaining transparency about benefits, risks, and limitations of dietary approaches.

- Professional boundaries: Recognizing when nutrition concerns overlap with psychological issues requiring specialized care.

Cultural humility represents an essential approach for nutrition professionals working with diverse populations. This perspective acknowledges the limitations of one’s cultural understanding and emphasizes continuous learning rather than assuming mastery of other traditions. Practical applications include incorporating familiar foods into recommendations, adapting educational materials to reflect cultural diversity, and involving community members in program development.

The distinction between dietitians and nutritionists carries significant ethical implications in many regions. The terms ‘dietitian’ and ‘nutritionist’ are not interchangeable in all countries; in some places, the title ‘dietitian’ is legally protected. This protection helps safeguard public health by establishing minimum educational and professional standards. Consumers benefit from understanding these distinctions when seeking nutrition guidance.

Addressing Malnutrition and Obesity

Contemporary nutrition challenges manifest in seemingly opposite but related conditions: malnutrition and obesity. These conditions can coexist within communities, households, and even individuals. Malnutrition can result from both inadequate and excessive nutrient intake. [#6] This dual burden complicates public health responses and requires nuanced approaches.

Factors contributing to these nutrition challenges include:

- Food environment changes: Increased availability of energy-dense, nutrient-poor foods alongside decreased access to fresh, whole foods in many communities.

- Socioeconomic constraints: Limited financial resources that restrict food choices and may prioritize caloric density over nutritional quality.

- Time pressures: Modern lifestyle demands that reduce opportunities for food preparation and shared meals.

- Marketing influences: Persuasive advertising that shapes food preferences, particularly among children.

- Psychological factors: Stress, emotional eating patterns, and disordered relationships with food that affect consumption.

Addressing these complex challenges requires multi-level interventions. Individual education and counseling provide necessary knowledge and skills but prove insufficient without supportive environments. Policy approaches—such as food labeling regulations, school meal standards, and economic incentives for healthy food production—create contexts that facilitate better choices. Community-based programs bridge these levels by building local capacity and addressing specific neighborhood needs.

Weight stigma presents a significant barrier to effective nutrition care. Prejudice against individuals with higher body weights permeates healthcare settings and can discourage people from seeking nutritional guidance. Weight-inclusive approaches focus on health-promoting behaviors rather than weight as a primary outcome, recognizing that body size reflects numerous factors beyond individual control. This perspective shifts emphasis toward sustainable lifestyle practices that support overall wellbeing.

Early intervention shows particular promise in preventing nutrition-related health problems. Childhood represents a critical period for establishing food preferences and eating patterns that may persist throughout life. Programs targeting pregnant women, infants, and young children can influence developmental trajectories and potentially reduce future disease risk. These interventions often produce the greatest return on investment in terms of health outcomes and economic benefits.

The complexity of nutrition challenges necessitates collaborative approaches across disciplines. Nutrition professionals increasingly work alongside behavioral scientists, urban planners, economists, and policy experts to develop comprehensive solutions. This interdisciplinary perspective acknowledges that food choices occur within systems shaped by numerous influences beyond individual knowledge and motivation. By addressing these broader determinants, nutrition interventions can achieve more substantial and lasting impacts on population health.

Conclusion and Future Directions

[Source: depositphotos.com]

Summary of Key Points

The field of nutrition and dietetics stands at the intersection of science, healthcare, and daily human experience. Throughout this exploration, we’ve examined how nutritional science provides the foundation for understanding the complex relationship between food and health. From the fundamental principles that govern nutrient metabolism to the practical applications in clinical and community settings, nutrition professionals apply scientific knowledge to improve lives.

Several themes have emerged across our discussion:

- Evidence-based practice: The importance of grounding nutritional recommendations in rigorous scientific research rather than anecdotes or trends.

- Individualized approaches: Recognition that nutritional needs vary based on age, health status, genetics, and numerous other factors.

- Holistic perspective: Understanding that nutrition exists within broader contexts of culture, economics, psychology, and environmental systems.

- Preventive focus: Acknowledging nutrition’s role in preventing disease and promoting wellness before health problems develop.

- Interdisciplinary collaboration: Appreciating how nutrition science connects with other fields to address complex health challenges.

The educational pathways in nutrition and dietetics prepare professionals with both theoretical knowledge and practical skills. These qualifications enable practitioners to translate nutritional science into actionable guidance for individuals and communities. Whether working in clinical settings, public health agencies, food industry, or education, nutrition professionals serve as bridges between research and real-world application.

Potential Developments in Nutrition Science

The future of nutrition science promises exciting advances that may transform how we understand and apply dietary knowledge. Several emerging areas show particular promise:

- Nutrigenomics: The study of how genes and nutrients interact is advancing rapidly. This field may eventually allow truly personalized nutrition recommendations based on genetic profiles, potentially optimizing health outcomes through precisely targeted dietary interventions.

- Microbiome research: Growing understanding of gut bacteria’s role in health is revealing how diet shapes our microbial communities. Future applications might include specific dietary protocols to cultivate beneficial gut bacteria for improved immunity, metabolism, and even mental health.

- Advanced biomarkers: New technologies are enabling more sophisticated measurements of nutritional status and metabolic responses. These tools may provide more accurate assessments of how individuals respond to specific foods, moving beyond general guidelines to precise nutritional monitoring.

- Sustainable food systems: Research integrating nutritional adequacy with environmental impact will likely expand. This work aims to identify dietary patterns that simultaneously support human health and planetary wellbeing.

- Digital nutrition tools: Artificial intelligence and machine learning applications are beginning to transform nutrition assessment and education. These technologies may eventually offer accessible, personalized nutrition guidance at scale.

Technological innovations will continue reshaping how nutrition information is collected, analyzed, and delivered. Wearable devices that monitor physiological responses to food, smartphone applications that provide real-time dietary feedback, and integrated health platforms that connect nutrition data with other health metrics represent just the beginning of this transformation. The challenge for nutrition professionals will be integrating these technologies while maintaining human connection and contextual understanding.

The Evolving Role of Nutrition Professionals

As nutrition science advances, the roles of dietitians and nutritionists will necessarily evolve. These professionals face both opportunities and challenges in the coming decades:

- Expanded scope of practice: Nutrition professionals may assume greater responsibilities in healthcare teams, particularly in preventive medicine and chronic disease management.

- Specialized expertise: Increasing complexity in nutrition science may drive further specialization, with practitioners developing deep knowledge in specific areas like sports nutrition, pediatrics, or gerontology.

- Communication in information-rich environments: As nutrition information proliferates, professionals must become skilled at helping people navigate conflicting claims and information overload.

- Policy advocacy: More nutrition professionals may engage with systems-level change through policy development and implementation.

- Global health contributions: Addressing worldwide nutrition challenges will require culturally adaptable approaches to both undernutrition and diet-related chronic diseases.

The demand for qualified nutrition and dietetics professionals continues to grow as public awareness about diet’s role in health expands. This trend reflects broader recognition that dietary choices significantly impact both individual wellbeing and public health outcomes. As healthcare systems increasingly emphasize prevention, nutrition expertise becomes more central to comprehensive care models.

Professional education in nutrition will likely incorporate more interdisciplinary elements, preparing practitioners to collaborate effectively across healthcare and public health sectors. Training may place greater emphasis on communication skills, behavior change techniques, and cultural competence alongside traditional scientific knowledge. These adaptations will help nutrition professionals address the complex factors that influence eating behaviors.

For individuals interested in maintaining good health, understanding basic nutrition principles remains valuable regardless of scientific advances. Learning to read food labels, recognize reliable information sources, and develop sustainable eating patterns provides a foundation for navigating dietary choices. While specific recommendations may evolve with new research, the core principles of variety, moderation, and nutrient density continue to guide sound nutrition practice.

The future of nutrition and dietetics ultimately depends on balancing scientific rigor with practical application. As our understanding of food’s impact on health becomes more sophisticated, so too must our approaches to translating this knowledge into meaningful guidance. By combining cutting-edge research with compassionate, person-centered care, nutrition professionals will continue making essential contributions to human health and wellbeing in the years ahead.

References

- 1. Minor, Nutrition and Dietetics

https://steinhardt.nyu.edu/degree/minor-nutrition-and-dietetics - 2. Human Nutrition: Science for Healthy Living

https://www.mheducation.com/highered/product/Human-Nutrition-Science-for-Healthy-Living-Stephenson.html - 3. Nutrition and Dietetics, MS | Pace University New York

https://www.pace.edu/program/nutrition-and-dietetics-ms - 4. Nutrition Science

https://www.farmingdale.edu/curriculum/bs-ntr.shtml - 5. Nutrition, Dietetics and Food Science: Differences and …

https://degree.astate.edu/online-programs/healthcare/ms-nutrition-and-dietetics/non-registered-dietitian/differences-and-similarities-of-dietetics/ - 6. Nutrition For Healthy Living

https://www.mheducation.com/highered/product/Nutrition-For-Healthy-Living-Keck.html